Norddeich Radio During the 2’nd World War 1939-1945

Heartfelt thanks to Richard

Brunner, Foxboro, MA (U.S.A) for translating these pages to English.

In the autumn of 2003 I decided to add a section on Norddeich Radio during WWII to my Web site. I quickly encountered limits; there were no surviving official records of

that time, as they were destroyed shortly before the end of the war. The last living witnesses are also disappearing. From my esteemed shift leader with Norddeich Radio, Guenther Lueken,

recently deceased, I have only short recordings and hand notes from personal conversations. Friedrich Janssen, who was in 1943 a 17 year old "Luftwaffenhelfer" ( German Air

Force Helper) engaged at the Transmitting Station Norddeich and after the World War II became the Technical Manager of the Receiving Station Utlandshörn, and Klaus Goritzki, a naval soldier

assigned to Norddeich, both gave me valuable information.

An outstanding

and rare document published on occasion of the 50’th year anniversary of Norddeich Radio in 1957 was invaluable, and upon it the following is based. The authors of those lines may foregive

me that I took the text in part – if they still live…

The documents on the activity of Norddeich Radio during WWII and the entire correspondence with the supreme command of the navy (OKM)

were burned (briefly, before occupation by British troops) in May 1945. The report on the events affecting the largest coastal station is supported therefore mostly by personal records.

|

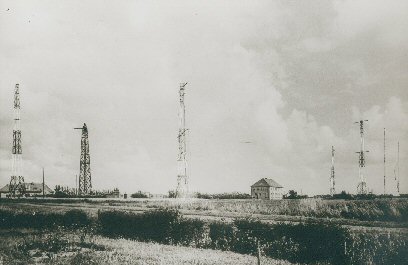

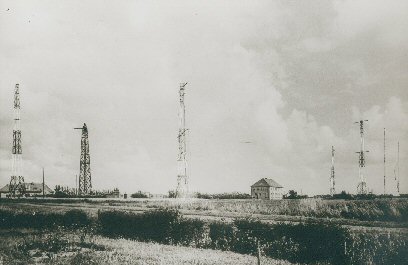

In the autumn of 1939 the main radio station Norddeich consisted of the transmission site Norddeich, reception site Utlandshörn,

and the large transmitter site Osterloog. The transmitter Osterloog was the newest site, established in the summer of 1939 about 5 km northeast of the town Norden. It worked in the band 400

to 1000 kHz with an output power of 100 kw. The antenna system was aimed toward central England, and consisted of two self-supporting 150 meter masts, four smaller directors and four

reflectors. Its transmissions consisted almost exclusively of foreign language programming from Berlin Test transmissions began on October 5’th 1939, first on 759 and 904 kHz, and later on

658 kHz. All three sites received a military guard at the beginning of the war. The three sites went through the war years without substantial damage. |

Neither Norddeich or Utlandshörn were ever attacked by hostile flyers; only Osterloog received a

string of bombs from an individual airplane, which however did not hit the station. Officers of the British air force later reported that Norddeich Radio had been spared because the English

intelligence service could determine from the types of transmissions whether German ships were still at sea.

At the outbreak of the war the personnel at Norddeich Radio were considered indispensible, and only in the autumn of 1944 a large

part of the staff was drafted into the Wehrmacht, of which only three returned. Early on, only three service routes stayed open. In the years 1940-1941 25 candidates, seamen from the Baltic

and Mediterranean seas, and the Norwegian coast, came to Norddeich Radio for further training, and Norddeich Radio was thus able to resume maritime mobile services without restriction,

which is important for safety of shipping, in addition to tasks in naval warefare guidance. The technical excellence and knowledge of high frequency propagation won over the years quickly

made it possible to communicate with any ship worldwide on the high seas. Use was made of this ability in the high-stress political spring and autumn of 1939 for passing instructions to

German trading vessels via code groups “QWA.” The first message was sent in March 1939 when German

troops invaded Czechoslovakia. |

|

In the middle of August 1939 two

telephone lines between Norddeich Radio and the OKM were installed, and shortly thereafter a lieutenant commander and “teleprinter upper-private-first-class” appeared, to send weather

reports and the location of ships to the OKM. In the night of 24 to 25 August 1939 Norddeich Radio sent two QWA telegrams pertinent to the beginning of the war, followed up with the

beginning of the war with England on September 3’rd 1939. After the first telegrams were sent, short-wave traffic with German ships was immediately suspended. Nevertheless, continuous guards

were maintained to the extent possible in order to not miss possible calls. German ships stood under steam and tried to reach either the homeland or the port of a friendly nation, and nearly

all succeeded. Remembered are the African passenger ships “Adolf Woermann”, “Ussukuma”, “Wahahe”, and the banana steamer “Poseidon” for communication with Norddeich Radio that it had been

attacked by hostile forces. The “Poseidon” traveled from Argentina, and had trouble just before reaching its goal of Denmark. The ship was in communication with Norddeich for 12 hours before

it was sunk by its crew.

|

Immediately upon the outbreak of the war, a naval commander became the Marine Arranging

Officer Norddeich, (MNO) and the personnel of Utlandshörn and Norddeich were engaged by the MNO for the services of the OKM. Officers and crews were accommodated in two barracks in the area

of the reception point. From the day of the outbreak of the war all messages had to be submitted to the arranging officer, (MNO) who passed them on to the OKM The soldiers of the naval

command in Norddeich at first performed only observation duties. Since the OKM became the immediate communication link with the auxiliary cruisers, which wanted to

communicate with supply ships and blockade runners, the production management of Norddeich Radio set up frequency plans and a transmission procedure to guarantee secrecy. The transmission

procedure was similar to the usual intergovernment radio traffic of trading vessels, and since naval radio operators were not familiar with this traffic, on suggestion of Norddeich Radio two

trading vessel radio operators were given to each of these ships. |

In addition, the radio personnel of the auxiliary cruisers were given detached duty to instruct them about the use of the plans and

transmission procedures. Shortly before running out the first auxiliary cruiser, the OKM decided on short notice to change the transmission procedure to zero-beat procedures, usual for the

navy. This procedure had the disadvantage that nearly every ship contacting Norddeich Radio could be located by sometimes six or more hostile direction-finding sites. In addition, it

permitted the hostile observers to determine frequency and transmission time.

|

|

|

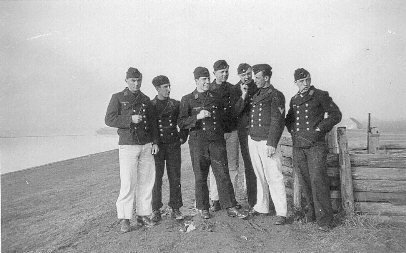

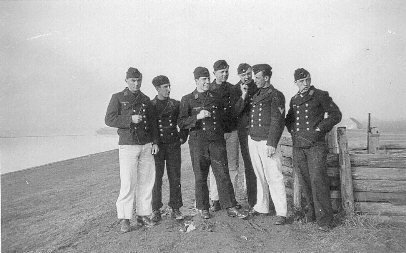

| Soldiers of the German Navy

Radio Corps in front of one of the barracks between the dike and the

receiving station Utlandshörn. |

|

The commanding officer with his

officers, petty officers and soldiers in front of the receiving station

Utlandshörn. On the right side the main entry. The soldiers with grey

uniforms are common soldiers to guard the area and the buildings. |

Everyone concerned with this enterprise will agree that the supreme command of the navy committed a fatal error

here. Did the navy for its surface ships at the beginning of the war use the so-called “side-frequency radio,” wherein ships worked on other, daily changing frequencies that the naval shore

stations? The German submarines and naval shore stations worked on the same frequencies, and the allied Huff-Duff automatic direction finders were on British units starting in 1941, and on

all the allied ships from 1943, which was deadly.

No-one was safe from direction-finding, and the German submarines were effectively pin-pointed and destroyed. The production

management at Norddeich Radio prepared a transmission procedure which made it difficult to focus on the German ships, which worked. The plan was, among other things, to run 150 Watt beacons continuously

in each frequency range at Norddeich Radio so radio operators on board ships could determine their most favorable frequencies. The 150-W-transmitters were operated with antennas

which were similar to ships antennas ( long wire ). These transmitters were also called "Alpha-Transmitters", because they transmitted a loop with the (German) morse letter "Alpha" ( ..-.. )

Since the auxiliary cruisers were exclusively in the South Atlantic, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific, on average 10,000 km or more from the homeland, this was an extraordinary help in facilitating fast transmission of messages. Later, Norddeich

Radio was used for communication with other parts of the fleet, including submarines. . |

Click here to enlarge the sketch |

|

The statements of Guenther Lueken and Klaus Goritzki essentially agree on the execution of radio traffic from Norddeich Radio. Contents of the naval messages

were naturally secured with the "M-Code." (naval code) The encoding keys changed typically once per hour, or at a minimum daily. Depending on the time of day, season, and propagation

conditions, the transmission took place on different frequencies in conformance with a defined listening and transmission plan. The hourly operating sequence is shown in the diagram. At the

designated times the blind transmission from Norddeich Radio was stopped, and ship messages were received on their frequencies. The ship messages were coded and radiated blindly as a very

short signal. Acknowledgment was not direct, but was in the following blind transmission from Norddeich Radio. The contents of the blind transmission were primarily military, but also

contained messages for crew members from people ashore. If nothing was available to be sent, the "empty time" in the blind transmission was occupied with "Filling radio," i.e. fictious

groups of letters, to confuse the enemy. |

Another help for ships at sea was a key in the CQ tapes for the beacons showing good or

bad transmission and receiving conditions. Günther Lüken told me – very interesting – that in spite of the war, civil radio traffic never completely ceased. Very often

Swiss hospital ships called Norddeich with so-called “government telegrams,” but he could not remember the ship’s names.

By the way, in event of Norddeich and Utlandshörn falling by enemy action, there was a receiving station in Muiderberg, near Amsterdam,

and a transmitting station in Kootwijk (Holland) supported by Norddeich Radio throughout the war.

Guenther Lueken

confirms that for a short time during the war he was sent to Muiderberg. The technical equipment, receivers, etc, was approximately the same as at Utlandshörn. He remembers that the staff

of the German "Reichspost" wore civilian clothes, but carried an arm band labeled "Deutsche Wehrmacht" (German Armed Forces). Probably this was to lend them the status of a soldier and place them under the

protection of the German military law.

Klaus Goritzki, 1942, shortly before he was detached to Norddeich Radio |

In Norddeich, apart from the military tasks, the special services such as weather service, and blind transmission, were

continued. At the beginning of 1940, a 5 kw medium-wave transmitter which could be operated by remote control from the reception site was installed. Starting in 1940 the central and long

wave transmitters had to be switched off immediately on instruction of the MNO if hostile bombers were approaching. They had determined that the bomber squadrons had used this Norddeich

transmitter for location for their many attacks on Emden and Wilhelmshaven in the first two war years. In addition it must be mentioned that starting from 1943 the British and American

bomber squadrons flew almost unhindered over East Frisia and the Ostfriesischen

Islands at great height, and the flak batteries on the Ostfriesischen

Islands with 8.8 cm and 10 cm cannon

could not shoot high enough. The flak exploded harmlessly below the planes. In the interior they met the few German interceptors and concentrated flak fire if they had to go lower for a bomb

release. Klaus Goritzki, who served as a soldier for a time at Norddeich reported that in the summer 1942 a heavily damaged American bomber from a daylight attack on Wilhelmshaven fell in the vicinity of

Norddeich Radio, and only one American flier with a parachute could save himself. A motorcycle rider drove out to the landing site, picked up the flyer, who had hurt his leg in the landing,

and returned to Norddeich. |

The flyer was given first aid, and the police station in the nearby town of Norden was called to take him to a

prisoner-of-war camp. Two police-men

came. They urged the American to the car with drawn pistols, though he could hardly move without assistance with his hurt leg. The naval soldiers loudly protested that he could not go,

whereupon one police-man directed his pistol at the soldiers and said, “you can come along

directly with me if you say another word.”

Naturally the English and German coastal stations radio behavior was very correct. In the first war years several times messages

were exchanged over shot airplanes, naturally only on instruction of the highest command posts, but under all customary radio procedures. An example of the fairness with which such cases

were treated at the time, is when the famous English flyer of WWI, Wing Commander Bader was shot down and his artificial leg became useless. Norddeich Radio gave this message to the English

station Humber Radio, and inquired whether forwarding of a spare artificial leg would be possible. After some time Humber Radio announced that they would procure a spare leg for Commander

Bader, and it would be flown over France and dropped by parachute. They indicated the type of plane, the route and flying time, and asked for German fighter protection.

The supreme command gave Norddeich Radio its assent to this action, reiterating the time, air lane, drop area, and the types of German

planes which would take over escort on the way in from the channel, and back. |

Soldiers of the German Navy Radio Corps on the dike close to

the Receiving Station Utlandshörn in 1940. In the mid Klaus Goritzki. On the right side an anti-aircraft stand with an antediluvian pedestal for an ancient water cooled machine-gun from World War 1. |

To protect against hostile airplane attacks, all three radio sites had light Flak batteries (2

cm-Flak 38), in October 1943 they were replaced by 2 cm-Quad-Flak, but they rarely took a shot.

Once,

however, in the summer of 1944 there was a favorable opportunity that could not be passed by. A 15 Ton whale had swum into the flat water and could not swim back to the sea. The dismantling

of this nearly 9 meter long animal brought a welcome increase in the meat and fat rations for the men of Utlandshörn. Only the commanders of the Flak batteries did not benefit from this

auxiliary food. They had to consider for a long time how they could prove the whereabouts of their fired projectiles from the forward battery. One witness wanted it known that this whale was

first identified as a British submarine, and only then fire was opened on it. Further, all the people who ate this “special food” came down with day-long diarrhea.

Klaus Goritzki ( 80 y. o.) remembers |

The extremely snowy and cold winter of 1941/42 made life difficult for radio station personnel. The road from the north and

Utlandshörn had become impassable with snow drifts up to 1.5 meters high, and the changing of the watch was ever more difficult. The staff needed three hours or more to trudge eight

kilometers, thus the watch change was stopped, and they tried to improve the scarce rations problem by getting milk from the neighboring farms. Several times they tried to clear the way

with the help of people from Westermarsch, and the military units, but one night of the howling east wind was sufficient to undo everything. Eventually we procured a horse-drawn sleigh, and

the staff was relieved at least every 48 hours. At the end of 1944 the front moved closer, and extensive precautions for protection of the station were taken. Around the stations double

fences were put in, machine gun emplacements were developed, and ditches were dug, as well as one-man holes. In event of an emergency, the instructions were to destroy the station by

breakup. Even important parts of civilian objects should be broken so they could not fall into the hands of opponents. |

At the beginning of 1944 about 1000 kg of high explosives was placed at each of the three radio locations. It formed a

constant danger for the main radio station in the last weeks of the war because of the activity of low flyers. At the urging of the production management, the MNO moved the explosives about

14 days before the end of the war to a camp to the north, where it exploded due to the imprudence of some solders, causing great glass damage in a nearby city. When the war ended, the front

stood about 30 km southwest of Norddeich. Important spare parts, wiring diagrams, reserve receivers, and other material were sent to the post office Sulingen, Bremen, where it fell to the

hands of the enemy.

Norddeich Radio was operational ‘till the end. On May 6’th 1945 British troops entered the city to the north, and at the same

time the transmission sites Norddeich and Osterloog. The English had at first no knowledge of the MNO command post, and Utlandshörn maintained continuous telephone contact with the other

two sites despite occupation. On May 12’th the receiving site Utlandshörn was also occupied.

Fritz Janssen quotes a contemporary: At first the British occupied the Transmitting

Station Norddeich and forbade the German personnel to operate the transmitters. When they later saw that some transmitters were operating, and the lamps on the front panels of the

transmitters flared in rhythm with the Morse signals, they asked for the reason. The answer was that the transmitters were remotely controlled and operated by the Receiving Station in

Utlandshörn. Thereupon they smashed the transmitting valves and drove quickly to Utlandshörn. Norddeich received the last instruction from the German military on May 8’th 1945. The German

commander sent an instruction from the British Navy to the main radio station that all German war and trading vessels at sea should sail to German and English ports. This was not possible

because the day before a British major had opened the main switch at the transmission site and decreed the death penalty if it were restarted. All efforts to make the British responsible for

the power cut were unsuccessful; all British command posts in the north, and also at Emden explained that they were not responsible. Also, British naval officers who were searching for

documents at Norddeich rejected restarting. Service work on the sites continued at a reduced level, and consisted mostly of maintenance. Only at the reception point, monitoring the emergency

frequencies went on uninterrupted. The next few days passed calmly. On May 2’nd the staff at Norddeich had to leave the station because they (the Brits) were looking for a secret

transmitter. |

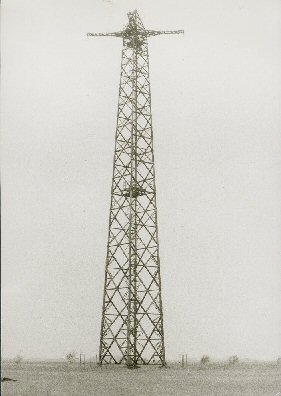

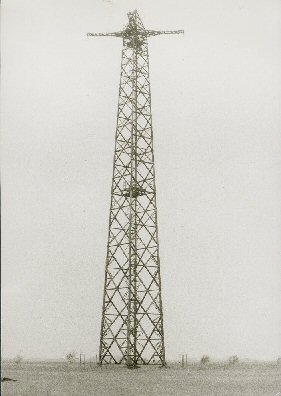

"Wooden Mast". This omni-directional Receiving

Antenna was in service from 1935

- 1976 |

On May 27’th the commander and officers of the 1’st Field Broadcasting Unit visited all three sites, and

decided that radio traffic would not be resumed. At the end of June rumors surfaced that Norddeich and Utlandshörn would be blown up.On July 12’th the regional directorate inquired about the staff, and said we should not count on resumption of the

enterprise. On July 16’th a telex came from the regional directorate by which half the staff would be delegated to the board of

works Bremen, and half to the board of works Oldenburg. One hour later a British colonel arrived in Norddeich, and explained that the radio station was not to be blown up, but immediately

placed in service, and the entire staff was ordered to the transmission site to clean up and set things in order. Well, by that time there had been lots of destruction, and the transmitters

were mostly broken glass, and destroyed instruments and parts. From Leer/Ostfriesland and Oldenburg tubes and parts were found, and after about 8 days Norddeich announced to the P & T

Branch, Control Commission for Germany, to the director of the radio section, with the seat in Luebbecke (Westphalia) that transmitter No. 1 and four other short-wave transmitters were ready

for operation.

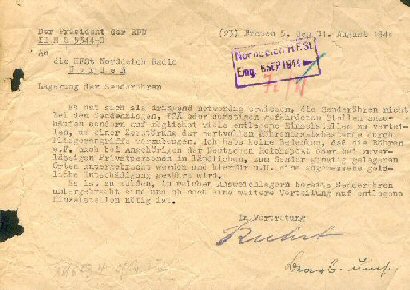

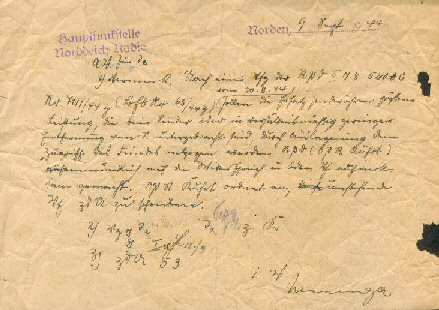

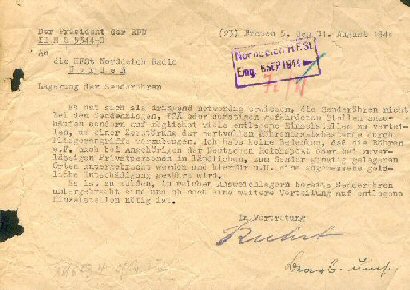

Rare document: A decree of the "Reichspost Direktion" in August

1944 to store all transmitting valves at nearby farms and private houses due to the risk of allied air attacks. |

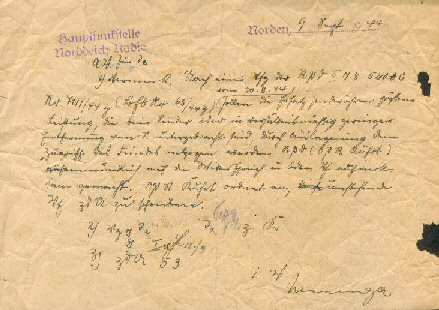

Handwritten comment on the backside. Gottfried

Nanniga, manager of Norddeich Radio, decided that the decree is impracticable.

(Typical "German Office Correspondence") |

By day one a british second lieutenant took over

as British Officer Commanding (BOC) with his office at receiving site Utlandshörn. In the next months good progress was made on repairing the transmitters, however Norddeich could not yet

return to the maritime mobile service. The first two transmitters that were finished were the 20 kw short-wave # 2 and 5. With them, at the beginning of August 1945, Hellschreiber and

telephone circuits with London were accomplished. Subsequently this became the point to point news service between Hamburg and London. In August 1945 four 5 kw short-wave transmitters from

the former German navy, and in September 1945 a 20 kw mobile long-wave broadcasting transmitter arrived at Norddeich. The director of the radio section ordered completion of the old

long-wave transmitter #1, which was well known to the ships at sea as “Anna,” and on October 5’th. it went into Hellschreiber service with the German News Service on 125 kHz. Also the four

short-wave transmitters were removed. At the end of September 1945 transmitters # 3, (2190 kc) #10, (3015 kc) and #11 (10,050 kc) were grouped as Elbe Weser Radio, controlled from Cuxhaven.

At the end of November 1945 the following transmitters were dedicated:

101 News broadcast

102 Point to point, German News Service

103 Shore Service

108 Commercial marine service

109 Safety wave

110 Shore Service

111 German mine sweeper service

112 Point to point, German News Service

The reception site Utlandshörn was used for monitoring medium waves and English amateur transmissions, and maritime emergency frequencies were

still monitored. The technical personnel of the 1’st FBU were withdrawn to Hamburg during October and November 1945 and replaced with German personnel, under BOC responsibility. Then, the

British agency was withdrawn in May 1946, and Norddeich Radio was again in German hands.

Return to Index Page